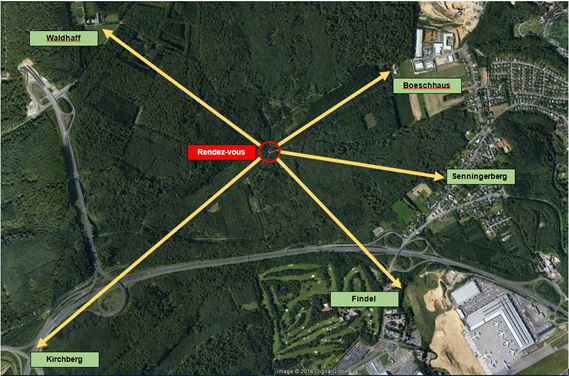

The «Rendez-vous» meeting point is the name of the place where the 5 ways leading to Senningerberg, Findel, Kirchberg, Waldhaff and Boeschhaus come together in the middle of the Grünewald. At times when crossing the Grünewald still was a dangerous adventure, locations like this had always been meeting points or important marks.

The «Rendez-vous» meeting point is the name of the place where the 5 ways leading to Senningerberg, Findel, Kirchberg, Waldhaff and Boeschhaus come together in the middle of the Grünewald. At times when crossing the Grünewald still was a dangerous adventure, locations like this had always been meeting points or important marks.

Not far from this meeting point the forest rangers did construct a charcoal woodpile for exhibition purposes.

Not far from this meeting point the forest rangers did construct a charcoal woodpile for exhibition purposes.

The trade of the collier is a very old craft, going back to the Iron Age (1000 ‑500 a.Chr.) and consisted in transforming the wood into charcoal. Already at these times the iron ore or other precious metals were melted with the help of charcoal.

In fact the charcoal has the property to burn with a much higher temperature than the wood and also its weight and volume is less important, facilitating the transport and storing.

Until the 19th century charcoal had a very high industrial value in the sector of the iron ore processing, asking for huge needs of wood volumes. Entire forests had been lumbered for this purpose. In the Grünewald numerous charcoal woodpiles were active, in order to feed the blast furnaces in Dommeldage and Eich for example. It is only with the discovery of the mineral coal that the use of charcoal slowly diminished and had been replaced by the coke.

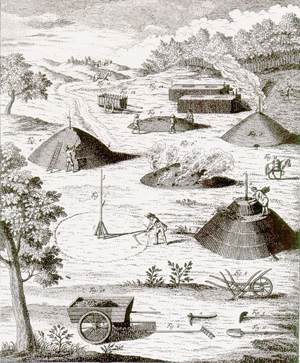

The collier’s charcoal wood pile

Representation of the different steps of the charcoal process.

The collier’s charcoal wood pile was erected immediately on the ground and with preference near to the waters (in case a fire had to be extinguished. First of all the collier had to dig a pit in which several wood poles were planted. Then 1m long logs were piled around this shaft in several layers in form of a cone. The wood pile had than been covered a roof of dry leaf, hay or straw and than hermetically closed by a thick layer of soil, grass and moss. Then the collier threw some hot embers into the shaft in order to light a fire going up to a temperature of around 300°C to 350°C, engendering the charcoaling process. The job of the collier consisted then in watching this fire for the next 6 to 8 days (or weeks if it was a very large wood pile) all by regulating the incoming winds to avoid that the fire went out or became to important. This could be done by perforating the pile with small holes that could be closed or opened according to requirements. The charcoaling process happened only under oxygen deficiency and with this method of opening and closing the little wind holes in the pile nearly 90% of the carbon could be preserved. Finally by closing all holes in the pile’s roof, the fire went out and the pile had to coo down. Then the charcoal could be taken out. 100 kg of wood gave approximately 25 kg of charcoal.

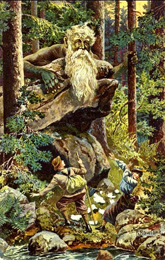

From the Middle Ages until modern times people were very afraid to find ghosts, brigands or thieves or eremites behind every tree in a dark forest. For this reason crossing the Grünewald to go to Luxembourg City at these times had always been a very frightful and dangerous journey for the locals. Nowadays the forest has mutated to a site of leisure and pleasure, to a precious habitat for fauna and flora.

From the Middle Ages until modern times people were very afraid to find ghosts, brigands or thieves or eremites behind every tree in a dark forest. For this reason crossing the Grünewald to go to Luxembourg City at these times had always been a very frightful and dangerous journey for the locals. Nowadays the forest has mutated to a site of leisure and pleasure, to a precious habitat for fauna and flora.